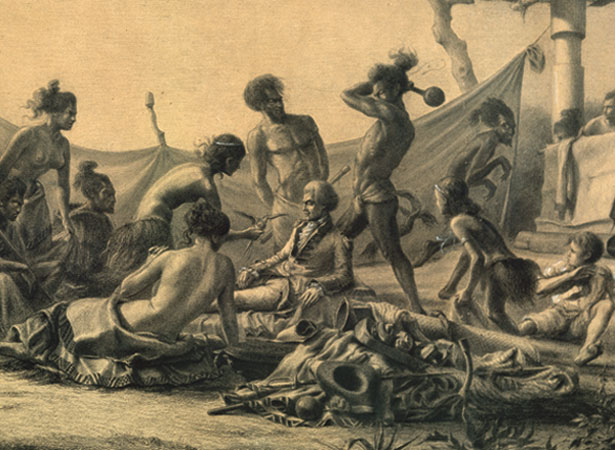

THE DEATH OF MARION DU FRESNE AT THE BAY OF ISLANDS, NEW ZEALAND, 12 JUNE 1772, BY CHARLES MÉRYON (1846-1848)

Charles Meryon, The Death of Marion du Fresne at the Bay of Islands, New Zealand, 12 June 1772,

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington (1846-1848)

I

Sometime between

1846 and 1848 drew the scene en graiselle

in pencil and crayon, heightened with chalk. It’s a largish work, one metre by

two metres – a heroic scale for a “heroic” subject, executed by the French

artist Charles Méryon (1821-1868)

and exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1848. Thence it passed on to the artist’s

closest friend, Antoine-Édouard Foleÿ (the two were stationed together at the

French naval base in Akaroa on Banks’ Peninsula), a member of the Paris

Positivist circle of the philosopher Auguste

Comte, who left it to his son. The drawing was purchased in Paris by New

Zealand-born British art collector Rex Nan Kivell, who smuggled it back to

London, rolled up in the leg of his trousers, as the Second World War broke

out. Eventually this magnificent curiosity entered the National Library of

Australia as part of the Rex Nan Kivell collection from 1959 until 1967 when it

was presented to the New Zealand Government by visiting Australian Prime

Minister Harold Holt. In December of that year Holt would go on a fateful ocean

swim and never be seen again.

Now in the

collection of the Turnbull Library, Wellington, the title of the work, The Death

of Marion du Fresne at the Bay of Islands, New Zealand, 12 June 1772, leaves very little ambiguity about the

subject. The Breton-born explorer and navigator Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne

anchored his ships, Marquis de Castries and Mascarin,

in the Bay of Islands from May to July 1772, late in the reign of Louis XV.

This was the first significant social interaction between Europeans and Māori,

and at first relations between the two were cordial enough, until suddenly they

weren’t. According to the story – particularly from what another French

explorer, Dumont d'Urville, was able to find out from local Māori during his

1824 visit to the Bay of Islands on the Coquille

- Du Fresne was killed by Māori of Ngāti Pou iwi beneath a Pōhutukawa tree at

Te Hue Bay before being ritually consumed by several local chiefs for his mana.

Méryon attempts to reconstruct the event, rather fancifully and through a

fictive scrim of overweening classicism. True to the tropes of the Picturesque,

the scene is set up like a stage. In the background Du Fresne’s ships are

anchored in the bay. In the mid-ground a French sailor takes a stroll with

Māori wahine, a reminder that sex often paid for European goods in early New

Zealand, and short-term marriages to Europeans for material gain would become

an important industry in some Māori communities. Unfortunately, this also had

the unforeseen consequence of unleashing a number of venereal diseases which

the indigenous tribes had no experience of or resistance to.

In the foreground, a scraggly Cordyline, looking like a refugee from a Dr

Seuss book, defines the left wing of the stage with its perky, calligraphic

line. The right wing is a pātaka, a storehouse for perishables raised on stilts

to protect it from the ravages of the Kiore, the native rat, and preserve their

tapu. Méryon’s interpretation of a pātaka is decidedly at odds with reality,

resembling more a ramshackle Roman temple out of a Piranesi engraving than

anything he would have seen in New Zealand. Essentially Méryon has put in the

barest of essentials to let the viewer know that this is a pā, a Māori village.

The effect was calculated to appeal to the contemporary vogue in French art for

exotic and decadent scenes with the plentiful bared breasts and poised,

theatrical violence.

The Death of Marion Du Fresne (detail)

To the left of the pātaka, in front of a palisade and draped backcloth,

Du Fresne presides over a déjeuner sur

l'herbe of Māori chiefs, warriors and wahine. In front of them is a pile of

Māori and European goods for trade. Méryon has depicted his countryman as a

dignified and noble hero of the Enlightenment in profile as one might find on a

coin. He is the calm, still focal point of the drawing’s universe. On the other

hand, Méryon seems like he can’t quite make up his mind how to depict the Māori

participants. Some resemble classical figures as one might find in the paintings

of Nicolas Poussin in academic postures fitting Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Noble

Savage model, or supine like an odalisque by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Others seem the worst racial and pantomime stereotypes, particularly the

rat-faced chap theatrically sneaking back to the pātaka while his tribesman,

suggestive of something from the orientalist paintings of Eugène Delacroix,

is paused mid-delivery of the dolorous blow with a club to Du Fresne’s powdered

scalp while a comely young wahine distracts the Frenchman with what looks like

a kākāriki, a small, green, native parakeet. A young, barefoot boy sailor,

about the age Du Fresne was when he first went to sea, turns to flee.

The fancy ten-dollar word for this little exercise is ekphrasis, the Greek word for

description, a literary description of a work of art.

II

Marc Joseph Marion du Fresne’s exact birthdate is unknown, but he was

baptised on 22 May 1724 in at the walled port of Saint-Marlo, Brittany, on the

English Chanel coast. The son of a merchant, in 1735, still a boy, Du Fresne

joined the French India Company ship Duc de Bourgogne as honorary

sub-lieutenant, which is the beginning of the trajectory that lead to his death

at the bottom of the world. During the messy War of Austrian Succession – a

complicated episode which managed to drag in all the European powers over the

question of Maria Theresa's succession to the Habsburg territories -

he commanded privateers out of Saint-Malo, rising to the rank of temporary

captain in 1745. After the ill-fated Battle of Culloden it was he who sailed to

Scotland to retrieve Bonnie Prince Charlie. He then served in the French royal

navy until taken prisoner by English forces in May 1747.

When the war ended the following year, Du Fresne served on several French

India Company ships, sailing to the Indian Ocean and China. With the outbreak

of the Seven Years War in 1754, he found himself a consultant for a proposed

landing by French forces in Scotland. With much cunning and daring do, he spent

two years in naval operations outsmarting the British blockade of Brittany and

in recognition of his skill and bravery he was promoted to fireship captain in

1759, and made a Chevalier of the Ordre

Royal et Militaire de Saint-Louis,

the immediate predecessor of the Légion d'honneur. After all that

excitement returned to trading in the eastern seas, conducting hydrographical

surveys of Mauritius, and for a time was harbourmaster of capital, Port Louis.

He also traded in the Seychelles and India, and participated in the peculiarly

colonial vice of land speculation.

The liquidation of the French India Company

caused Du Fresne considerable financial bother and when in 1771 the opportunity

arose to voyage to the Pacific on a trade and exploration mission sponsored by

the French government. This was in no small part sparked off by Captain James

Cook’s first Pacific expedition aboard the Endeavour which had returned

that year, with the hope that if there was a new continent to be discovered to

the south of New Zealand, the hypothetical Terra Australis Incognita, it should

be claimed by France, not Britain. Du Fresne was provided with two naval ships,

the twenty-two-gun Mascarin and the sixteen-gun Marquis de Castries. The first

directive of the mission was to return, like an overdue library book, the

Tahitian Ahu-toru to his island home. Ahu-toru had been brought to France in

1768 by Louis-Antoine de Bougainville. Lionised in Paris and becoming something

of a celebrity, this brave voluntary Polynesian explorer of Europe had been

sent to Mauritius to find passage back to Tahiti, the “New Cythera” of the

Pacific.

Du Fresne and his ships sailed forth from Port Louis on 18 October 1771.

This proved most opportune as an epidemic of smallpox had broken out in

Mauritius. Unfortunately, the disease also killed Ahu-toru. After picking up

supplies at the islands Bourbon and Madagascar, since the Tahiti was no longer

part of the mission, Du Fresne decided to try and recoup some of the expedition

costs by heading for Cape Town in South Africa to begin their search for the

Southern Continent in the high latitudes of that hemisphere. On the way he

discovered the south Indian Ocean islands of Marion, Prince Edward, and the

Crozets. After a stopover in Tasmania where he was the first European to

explore and interact with Aboriginal Australians, the mission set sail across

the Tasman for New Zealand.

They sighted Mount Taranaki on 25 March 1772, giving it the name Pic

Mascarin (not realising that Cook, who had been through on the Endeavour in 1769, had already named it

Mount Egmont after John Perceval, 2nd Earl of Egmont, a former First

Lord of the Admiralty. Sailing north on 15 April they landed at Spirits Bay.

Two days later strong winds severely damaged the ships, losing a number of

anchors, so they limped south-east and on 4 May reached the drowned valley complex

of the Bay of Islands, anchoring first to the south of Okahu (Red Head) Island

and then off Moturua Island.

The French had some idea of what to expect. In 1769 a previous expedition

let by Jean François Marie de Surville of the Saint Jean Baptiste had visited the area,

though had ventured no further south than Doubtless Bay and hadn’t left a

positive impression on local Māori as, following the theft of

a small boat, De Surville’s men had retaliated by the razing of a kāinga close to

shore, and the kidnapping of Ranginui, a Ngāti Kahu of rank. He would die at sea three months

later.

Du Fresne and his men spent a leisurely five weeks exploring the Bay and

making repairs to the ships. They set up camps – one on the mainland as a

quartermaster’s store and communications base, a tent hospital for sailors

stricken with scurvy on Moturua, where gardens were also planted, and one

inland in the forest to hew masts and spars for the ships. They were also able

to visit distantly scattered pā to trade, able to communicate by means of an

extensive Tahitian vocabulary put together by Bougainville and Ahu-toru,

sufficiently close to te reo Māori to be comprehensible, and despite the

occasional nuisance of what the French regarded as petty theft (Māori concepts

of property and reciprocity being very different to those of Europeans),

prospects appeared very pleasant and relations friendly. On 8 June Du Fresne

was even welcomed at a special pōwhiri in his honour by Te Kauri, chief of Te

Hikutu hapū, and four white feathers placed in his hair, denoting chiefly status.

This charmed Du Fresne, already an enthusiastic student of the culture, greatly.

What the Frenchman didn’t realise was that despite tranquil appearances,

he and his crew had arrived at an extremely fraught moment in Bay of Islands

history. They were sitting on a powder keg.

By the middle of the eighteenth century the Bay of Islands was like a

scaled down Māori

Mediterranean, populated by diverse hapū with modestly-sized territories scattered around the coasts and further

inland. Apart from the hapū to the north and south of the bay, most of these communities shared whakapapa.

Ngāti Miru and Te

Wahineiti occupied Te Waimate which stretched from the Kerikeri coast to the Waitangi

River. Ngāti Pou inhabited Taiamai,

the southern part of the Bay from Kawakawa and extending west. Ngare Raumati

controlled Te Rawhiti, the coast and remoter islands of the Bay’s southeast. North

and south of the bay were the territories of the various hapū of Ngāpuhi, and they had ambitions.

Around 1775 the Northern Alliance of Ngāpuhi hapū descended on the Bay, conquering Te Waimate. Two decades

later the Southern Alliance took Taiamai. Ngāpuhi cemented their absolute

dominion of the Bay over subsequent generations, beginning with a ferocious,

but ultimately unsuccessful attack on Rawhiti in around 1800, and an

overwhelming victory in 1826.

The Northern Alliance invasion a mere two years in the future, tensions

were running high. The presence of the French was destabilising in that

precarious environment. Less than a week after the pōwhiri, Du Fresne and the

fishing party he had gone ashore with were attacked and killed. A second party

was attacked the following day and four hundred armed Māori attacked the

hospital camp on Motorua, but were turned back by the overwhelming firepower of

French blunderbusses. In all, twenty-seven of the French died: two young officers,

M.M. de Vaudricourt and the volunteer Pierre Le Houx, the second pilot Pierre

Mauclair from St Malo, the steersman Louis Ménager from Lorient, Marc Le Garff,

also from Lorient, Vincent Kerneur of Port-Louis, Marc Le Corre of Auray, Thomas

Ballu of Vannes, Jean Mestique of Pluvigner, Pierre Cailloche of Languidoc, and

Mathurin Daumalin of Hillion. What we know of that fateful day comes from the

accounts of two officers, Jean Roux and De Clesmeur.

It has never been entirely clear what the trigger was. The Northern

Alliance invasion effectively disrupts the thread of oral history. The French

were already bulls blundering around in the china shop of Māori tikanga and

protocol, and their ongoing presence both created political, cultural and

economic issues for local iwi and carried with it the spectre of a permanent

French settlement. Some claim that they had violated tapu by fishing in Manawaora

Bay where the bones of the dead were cleaned prior to interment, or where the

drowned corpses of members of a local iwi washed up in Te Kauri’s Cove (now

known as Assassination Cove).

This story, appearing in the 1960s, seems rather unlikely. Supposedly the

French had been at the tapu beach for seventeen days, assuming they were still

in distant Ngāti Pou territory,

but in fact in Te Kauri’s lands, just below the pā. Discrediting this is the fact that Te Kauri was well

known to the French, having dealt with them on multiple occasions and having

been on their ships. It seems altogether more likely that this was a gambit by

one hapu or other to acquire muskets, or a response to the French being perceived

to have claimed Motorua. Following the pōwhiri for Du Fresne, Māori made a

nocturnal raid on the Moturoa hospital camp, taking muskets, uniforms and an

anchor. The French took two of the culprits hostage against the return of the

stolen property, one of whom accused Te Kauri of having been involved. Du

Fresne ordered the men released, but this even alone would have caused Te Kauri

significant loss of mana in a scenario where the French were already,

unwittingly, being used as pawns in a competition for status among local hapū.

Later an armed party of Māori, presumably Te Hikutu, challenged the French, but

utu was restored with an exchange of gifts.

In all that time there was no mention of tapu, but parties of Māori had

been seen by French sentries prowling at night around the hospital and lumber camps,

and visiting chiefs showed a great deal of interest in the French muskets and

blunderbusses. These visitors went so far as to ask for a demonstration which

was satisfied by Jean Roux, Ensign of the Mascarin,

shooting a dog. Those would have been powerful incentives for any enterprising

chief. French weapons and resources would have dramatically changed the balance

of power in the area as British muskets and the easy carbohydrates of potatoes

were for the following generation.

Following the attack on the hospital camp one of the local chiefs told

Roux that Te Kauri was responsible for killing Du Fresne. Soon longboats of

armed French sailors arrived to confirm that Du Fresne and the others had been

killed, apparently lured into the bush and ambushed. Despite it being the small

hours of the morning, according to Roux’s account he claims to have recognised

Te Kauri in the darkness and ordered him shot. In the days that followed, the

French came under persistent attack as more Māori reinforcements arrived. The French abandoned the

hospital camp, which was raided and razed to the ground. As they retreated to

Moturoa, the French were still close enough to see that the warriors wore the

clothes of Du Fresne and his fellow sailors.

That night Māori attacked the

Moturoa camp, this time to general fire from the French. The next day another

300 or so Māori joined

the attacking force, bringing it to around 1500 fighters, whom the French

charged with 26 of their own soldiers, seeing them off with technological

superiority. Gallic pride having taken sufficient battering, the French

attacked Te Kauri’s pā, being met with a rain of huata. Te Kauri’s allies fled

in their waka. Some 250 Māori were killed, including five chiefs, and many

French sustaining serious wounds.

On 7 July, investigating a month later, Roux found Te Kauri’s pā abandoned, the cooked head of a sailor on a spike,

and some human bones. Julien Crozet, Du Fresne’s second in command, and the captain

of the Marquis de Castries, Ambroise-Bernard-Marie

le Jar du Clesmeur secured their ships, to which the French withdrew, fighting

off small sporadic raids. In order to complete repairs on the ships, Crozet and

Du Clesmer ordered a counter-attack to clear the area of the lumber camp,

instigating reprisals resulting in a further 250 casualties among Māori.

These events left a profound scar on the French psyche. Before they

departed on 12 July for the Philippines, they buried a bottle

at Waipoa on Moturua, containing the arms of France and a formal

declaration of possession of “France Australe” in the name of France, but left

firmly of the view that Māori bore no resemblance to Rousseau’s “noble savage”

and the dangers posed by them warranted against any attempt at colonisation.

And yet they would attempt to do just that, and seventy-two years later a

French artist, familiar with New Zealand and its French colony at Akaroa on

Bank’s Peninsula.

III

Charles Méryon (1821-1868) is possibly not so well known a name these

days as he deserves to be, but is generally regarded as the finest French proponent

of the etcher’s art in the nineteenth century. He was born in Paris, a bastard,

the illegitimate son of a travelling English doctor and a dancer with the

opera. Méryon was raised by his mother until he enrolled at the Naval

School at Brest in 1837, eventually embarking of a tour of duty around France’s

possessions in the South Seas on the corvette Le Rhin.

Like William Blake, as a boy Méryon claimed to have seen troops of

angels around him. A brooding, melancholy sort, quick to take offence, Méryon was

already an accomplished draughtsman when Le

Rhin arrived in New Zealand in 1842, resulting in a remarkable series of

pencil drawings of the landscape. It was around then that his mother, suffering

from a mental affliction, died. Ostensibly Le

Rhin’s mission was to protect the tiny French settlement of Akaroa on Banks

Peninsula as Britain moved to consolidate control of the archipelago.

Akaroa (“long harbour” in the Ngāi Tahu dialect), founded in August 1840

by French settlers, is Canterbury province’s oldest township, lying 84

kilometres at the end of a winding and precipitous route southeast of

Christchurch. At around just over 600 people, sixty percent of the houses are

holiday homes. It retains a strongly French flavour in its architectural style,

the street names, and the occasional tricolor.

On the Rue Lavaud is a modern statue, intended to represent Méryon, but erroneously

depicting him as a stereotypical painter at easel and wearing a smock and beret.

By the time Le Rhin arrived, its

mission was largely irrelevant. Three months before the settlement had even been

founded (the French whaler Jean-François Langlois being under the mistaken

impression he had purchased Banks Peninsula from Ngāi Tahu), two Ngāi Tahu chiefs,

Iwikau and Hone Tikao (John

Love as he was better known to Pākehā),

signed the Treaty of Waitangi at Ōnuku on Akaroa Harbour. It had been Pākehā involvement in Te

Rauparaha’s 1830 raid on the area, leading to direct intervention by the

British, which lead to the Treaty process in the first place.

Méryon’s drawings of Akaroa, and the etchings made from them, are

fascinatingly detailed, and those made of the Māori village at Ōnuku clearly reveal the elements, in their

original organisation and with a Romantic eye for nature, that make up the more

Classical composition of The Death of Marion du Fresne.

Charles Meryon, Greniers indigenes et habitations a Akaroa, presqu'Ile de Banks (1860)

On his return to France, while only 25, still a lieutenant and with only

a tiny inheritance, Méryon left the navy with the ambition of becoming an

artist. It was only then, however, he discovered that he suffered from

Daltonism, a hereditary form of colour blindness that causes confusion of

greens, reds, and yellows, leading him to enter the atelier of the engraver Eugène Bléry, under whose tutelage he acquired

the technical skills of etching. Méryon

supported himself with hack work, when not copying the etchings of Dutch

masters like Renier Zeeman and Adriaen van de Velde, eventually going on to

produce the celebrated series (though never published as one) Eaux-fortes sur Paris from 1850 to 1854,

consisting of twenty-two etchings, collected together with the rest of the

artist’s oeuvre in the Victorian art critic Frederick Wedmore’s catalogue Méryon and Méryon’s

Paris (1878) in an edition of 129.

It is the studies of Paris, it’s glories and squalor (even as George

Haussman was tearing it down and replacing it with boulevards for Napoleon III)

that are the noblest fruit of his abilities, though there are some nice

illustrations of the wooden houses of Bourges, around 240 kilometres from Paris.

What Méryon might have accomplished had not material and mental

struggles not shortened his life, will never be known. His work failed to find broader

appreciation, despite the admiration of no less than Baudelaire, Gautier, and

Victor Hugo, and he was forced to sell his etchings (when he could sell them) for

a pittance. The poverty and disappointment played heavily on his mind, even as

his supportive friends, the etchers Félix

Bracquemond and Léopold

Flameng, became successful.

As Méryon’s own reputation slowly increased (Dr Paul-Ferdinand Gachet,

who cared for Van Gogh in that artist’s final weeks at Auvers-sur-Oise, was a

fan) he declined into paranoia, fearing imaginary enemies at every turn, believing

his friends stole from him or owed him money. When the English surgeon etcher

Francis Seymour Haden visited to purchase a set of the sur Paris etchings, Méryon’s chased him through the streets of

Paris, seizing back the etchings and accusing the startled Englishman with

wanting to plagiarise his work.

Eventually he became completely delusional. he started

digging up his garden looking for dead bodies, eventually taking to bed and brandishing

a pistol at anyone who attempted to see him - and was committed to the infamous

asylum at Charenton Saint-Maurice on 12 May 1858.

His stay in Charenton, the French Bedlam, restored him to some lucidity, and

was released for a time, resulting in some of his most visionary and peculiar

work. It is evident that his mind travelled back to the Pacific from time to

time, resulting in the striking Tourelle de la Tixeranderie, Ministere

de la Marin (1865), depicting the

offices of the French Admiralty, while in the sky above, a surreal flotilla of

Polynesians in canoes race against horse-drawn chariots, tiny like the staffage

of a landscape painting. These efforts exhausted him and he briefly returned to

Charenton in late 1866. He was released again in 1867 so that he could

visit the Exposition Universelle at the Champ de Mars and Ile

de Billancourt, where some of his etchings were being exhibited.

At this great world’s fair, only the second to be held in Paris, with 50,226

exhibitors (15,055 from France and her colonies, 6176 from Great

Britain and Ireland, 703 from the US, and even a

representation from New Zealand) the

likes of Jules Verne and Vincent van Gogh thrilled to such sights as the

hydraulic elevator, reinforced concrete, and a recreation of the reliefs of

Borobudur in the Java.

Alas, on the day Méryon visited, the weather went bad and a violent

thunderstorm struck, terrifying the fragile artist out of his wits and

shattering what remained of his sanity. He was once more committed to

Charenton, never to emerge. He came to believe himself the second coming of

Christ incarcerated by the Pharisees, and grew obsessed with the notion that

there was insufficient food in the world for its population. To that end he

began designing bedroom furniture that looked more like torture devices, for

the express purpose of preventing sexual intercourse that might lead to reproduction,

and refusing to disadvantage the poor by taking scarce food from their mouths, stopped

eating. He starved himself to death in February 1868.

IV

This is a fabulous work and a truly fascinating essay Andrew! Thank you so much for sharing.

ReplyDelete